Le Musée Picasso

A highlight of a trip to Paris last summer was a visit to the Musée Picasso. Having undergone years of renovation, the museum reopened October 2014. Recreating museums and giving old buildings new life is something the French do exceedingly well, without compare.

Eager beaver that I was, I turned up a full hour before opening time—Not until eleven, monsieur?—which gave me an excuse to linger over coffee at a small café, Le Saint Gervais, a block from the museum, at the corner of rue Vieille du Temple.

Taking a sidewalk table offered a chance to watch the neighborhood wake up, to listen to the animated male voices coming from within the cafe, and to keep an eye on an elderly couple catching the morning rays in a secluded park across the narrow street. All of which made for a quintessentially Parisian moment for this flaneuse/bloggeuse who likes nothing better than observing the lives of others from a distance.

At the appropriate hour, I returned to No. 5 rue de Thorigny in the upscale Marais, where the Picasso collection is housed in an exquisite 17th century building once known as the Hotel Salé, a detail of which can be seen below. The name Salé (meaning ‘salty’) refers to the revenues collected by the original owner, a monsieur Pierre Aubert de Frontenac, the collector of the salt tax for France—for all of France, that is. Judging from the style and size of his magnificent mansion, he must have salted away plenty of those old French francs.

The collection contains 5,000 works by Picasso, 3,000 of them on paper. There are also the 263 works that he chose to keep with him throughout his lifetime, including works by his friends—Corot, Degas, Derain, Le Douanier Rousseau, Miro, Cezanne, Matisse, Vuillard, Renoir, Braque, Balthazar and Apollinaire, to name but a few. Picasso, no shrinking violet, eagerly sought out the company and the work of other artists, none more so than that of Matisse. He capitalized on their ideas, as they did on his.

Early on, Picasso had a liking for African art as well as for the works by 'primitives,' those self-taught painters who were not classically schooled. Indeed, the 1895 ‘Portrait of a Woman’ by Rousseau (below, right), a self-taught artist, was the first work Picasso ever acquired. Of it he would say that it was the most psychologically truthful of all French portraits

Years later, he would trade a few of his own sketches for Matisse’s portrait of his own daughter, Marguerite (above, left), also on display at the museum. And ultimately Picasso would offer the artist the highest compliment saying: There is only Matisse.

There are so many great beauties here, including the magnificent main staircase and the galleries filled with light, great art and fascinating stories. At the top of the staircase is Head of a Woman, an early sculpture. Picasso's muse for this work was Marie-Therese Walter, whose beauty he said demanded a classical treatment.

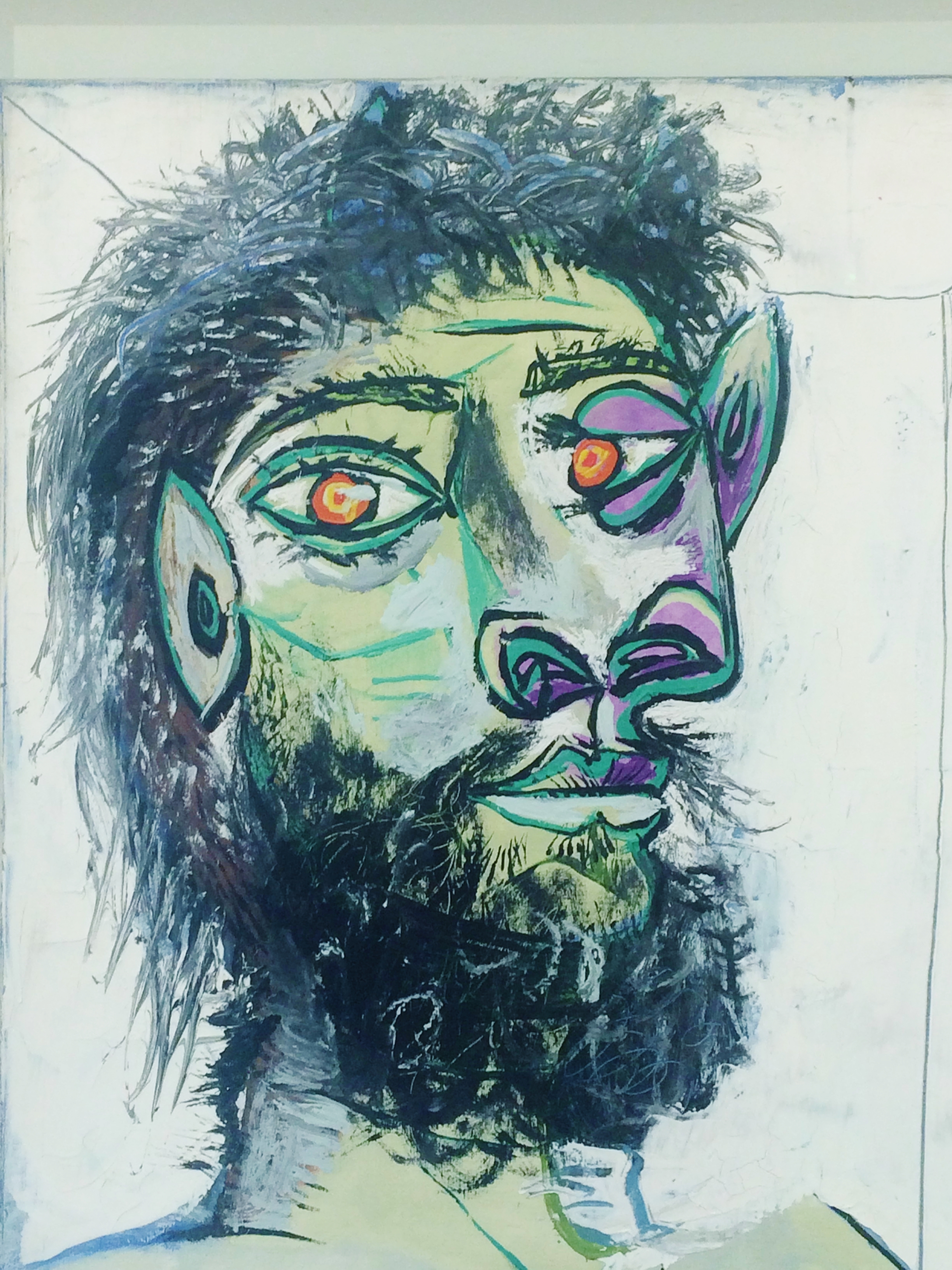

In the late 1930s, with the rise of Fascism in Europe, Picasso painted a number of portraits of his muse and mistress, Dora Maar. In Weeping Woman (1937), her expression is serene, even magisterial, but note the eyes, one facing forward, the other seen in profile. It's a puzzlement and a charm.

What’s remarkable is how many works from Musée Picasso are currently on display at MoMA in New York in a monumental exhibit: Picasso’s Sculptures. A show that the New York Times art critic Roberta Smith called 'a once-in-a-lifetime event.' But that I will save for yet another day.

And, lastly, I was charmed that day in Paris seeing Picasso's chair from his studio—a work both painterly and sculptural!

So which is it? Do you prefer paintings to sculpture? Watercolors or drawings? As you move from gallery to gallery, what is it that makes your heart sing? It hardly matters at the Musée Picasso, where I guarantee you there is something to please everyone, even the most discerning of critics.

So that's all for today, my friends. Hope to see you back next week, when I'll try to have something equally dazzling to share with you. Until then, may life be good to you.